“Strangetown, USA” Premieres on Culture Collide!

Strangetown, USA officially premieres! This is the text in full from the premiere article on Culture Collide.

In the wake of the harsh political climate that began after the 2016 election, Oakland-based avant-garde performance artist, Pancho Morris, chose to channel his distaste of the presidential election into writing a dark political dirge, rallying over 100 artists from the Bay Area to create a truly radical music video.

Culture COLLiDE is thrilled to premiere the bizarre and beautiful “Strangetown USA” from Pancho’s debut LP, Great Again. The video is a parody of America’s hedonistic tendencies tied to our current political and economic injustices, delivered by a joyously cinematic production. COLLiDE had the chance to sit down with Morris and his team to discuss how they pulled off the challenging task of wrangling a huge collective of creatives to complete a singular artistic vision.

How did you initially get everyone involved on the same page? Was there meetings, a mission statement, or did the song do all the talking?

When we decided to make “Strangetown, USA” as a collective, we knew we wanted to try something different — we wanted to do it by consensus, as much as possible. We were invited to the home of producers Chris Swimmer, Jen Johnson, and Ad Naka to have an open, “blue sky” discussion about the project.

In a traditional film production a director walks in, dictates a treatment, gets handed piles of cash, and you either get on board or you miss the train. We decided early on: our train wasn’t leaving without anyone. And so we sat together on the floor of a dimly lit room in a Haight-street San Francisco co-op, closed our eyes, listened to the song, and shared our unique visions. We saw weird, surreal, and dark. We saw a phone in a bird cage. Blood. Tired, exhausted eyes. Golden gates and golden keys. Extravagance. Pigs eating pigs. The heavy top of a fragile pyramid.

We asked Pancho what inspired him to write the song. He described the “this can’t be real” feeling of Trump being nominated for President, of “waking up in a country that no longer feels your own,” a country where, “truths lose their self-evidence, and your very existence becomes an act of treason.”

And so the challenge became determining our mission statement: how do we reconcile the artist’s original intent with a collective interpretation, and do so in a way that democratizes ownership? Our answer was to establish a “do-ocracy” whereby people were empowered to do what they felt compelled to, starting with the treatment. So we put the call out to writers. By the end of the review meeting (a long one), we had synthesized material from every submission into a master narrative, approved by unanimous vote.

We built and shared a simple website announcing the project and inviting our community to get involved. Before we knew it, we had momentum. The train to Strangetown was collecting artists from all corners — muralists and mask-makers, builders and butchers, aerialists and anarchists. The train was moving faster than we could lay track.

Did pre-production involve any movie screenings to create a reference for the overall vibe? If so, what were some of your essential aesthetic touchtones?

The major visual reference for the music video was the “grEAT aGAIN” album art by local artist Pp. Using the visual language of isotype, the jacket cover illustrates over 400 figures from current events and American history, assembled in a grand pyramid and engaged in various exchanges of power and moments of resistance. Gold figures, representing the 1% of Americans (who hold 90% of the nation’s wealth) are on top, and red figures, representing the 99% of Americans (who don’t), are on the bottom. Historical figures in the pyramid include Vladimir Putin, the President, Jeff Bezos, but also some true heroes — a kneeling Colin Kaepernick, abolitionists Harriet Tubman and John Brown, #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo protesters, Lakota water protectors, and over 50 members of the east bay arts community.

We agreed that we wanted to base the visual aesthetic on the album art, using simple colors to represent broad ideas. Use of the color red would be used to symbolize the working public, gold the elite, and purple the people and institutions that hold our current economic and political systems in place.

We knew Pancho would climb the pyramid through the “Red World” and into the “Gold World,” but the details of those worlds were still unknown. We intentionally left that space open for the community to fill; local artists submitted ideas for “vignettes” that fit into those worlds, supporting and expanding upon the themes we were exploring. This allowed many artists to have creative input while keeping our narrative and stylistic vision intact.

What was it like working with such a sprawling group of production designers and crew members? How did you avoid it all spiraling into chaos?

During pre-production, we ensured thematic continuity through extensive dialogue between our creative director, Sarah Duryea, our production designer, Treigh Love, and each of the “vignette leads” (who were responsible for the “mini-scenes” in the video). Sarah was the essential interface between vignette leads Mrk Davis, Garett Brown, Michelle Lessans, Michael Morgenstern, and Avi Dunn. She was responsible for making sure that, from a narrative perspective, each of their scenes were in conversation with each other, the treatment, and the album artwork.

While Sarah was focused on narrative, Treigh was responsible for making sure that all of the sets, all the props, the paints, the construction — everything that built the physical reality of Strangetown — worked cohesively. Lichen White and Kate Milazzo handled wardrobe and costuming for the entire cast. Day after day, truckloads of free would-be garbage were getting dropped off in the warehouse for potential use. E-waste centers were being raided. Dumpsters of prop houses were being dove. It was scrappy. It was punk. It was using what we had, throwing out the grand plan, and relying on trial and error.

Once everything was ready to shoot, the set operated like a more traditional film set. Eric Sheehan, 1st Assistant Director and longtime friend and colleague of both our director and cinematographer, stepped in from Los Angeles to become our team captain on-set. He was responsible for making sure everyone knew what was going to happen at all times. He and the production team would coordinate with our extensive cast, work through their “marks” and lock down the choreography of each sequence before and in-between takes. Behind the scenes, assistants would ensure golden money guns were always ready to pneumatically rain cash on Pancho in a moment’s notice. All the while, director Dillon Morris was keeping the set cool and calm, with morale high despite the long hours folks were graciously donating to the project.

What’s the most amount of takes the team went through, attempting those complex long shots?

Because the shots were long, moved through different physical sets, and needed to be choreographed to the music, we spent a lot of time rehearsing. We rehearsed both with and without the camera, one scene at a time, until we felt we had the timing, the camera movements, and the lighting just right. This allowed us to keep our recorded takes count averaging around 10.

Alleviating some of the complexity was the decision to keep the camera handheld, instead of using a complicated gimbal or large steadicam setup. This allowed cinematographer and camera operator Adam J. Richman (aka “Ready”) to have more direct control over each of the camera’s axis for framing and pacing. The final shot — a roughly 1.5 minute “oner” that weaves through multiple vignettes and dozens of performers in the “Gold World” — was by far the most dynamic and challenging. We took an entire day to stage and complete the finale of the video.

We held our breath, watching the monitor as Ready danced through the scene with the performers… We thought we had the perfect take when, just at the last moment, the camera snaps up towards the ceiling before crashing down! Ready, walking backwards through the dimly-lit warehouse, had tripped over a “dead” performer, ruining the final frame. At this point it was past midnight, and we were all exhausted to the core. Losing that shot was tough. But we shook it off, tried again, and the very next take seemed even better than the last — we all crowded the monitor for a replay, just to be sure… when we finally called wrap, the entire warehouse burst into cheers. It was an incredible feeling of accomplishment for the hard work of over 100 people to culminate in such a challenging and well-executed shot.

I’m curious about the wide ‘cinemascope’ look of the video. Why was this aspect ratio chosen and how was it achieved?

The idea to shoot the video at an unconventional extra-wide 2.40:1 aspect ratio, was an important decision in the early stages. Aesthetically, the aspect ratio complimented our desire to shoot wide (18mm), which allowed us to appreciate the elaborate sets. Logistically, the limited vertical room in the frame allowed us to mask the shorter-than-preferred height of the the flats we were gifted by Event Magic in Oakland.

Wider lensing and the use of handheld camera operation helped make the video feel more theatrical and alive, too. It captivates viewers as we walk with Pancho between worlds. The camera suggests the presence of the viewer in the video, showing the perspective of the audience shadowing our hero’s journey.

Further, by widening the frame, we were able to hide many little “easter eggs” within each of the scenes. Our vision was for all these details to add “replay value.” We wanted folks to feel like they missed things on their first watch so they had an excuse to dive deeper into the narrative and understand more of the complex intentions behind each of the vignettes.

Did you have enough room in the warehouse to construct all the sets at once? Or did you have to shoot one setup, break it down, and build a new one for the next sequence?

The warehouse was the final twist of the Rubik’s cube. When we began the journey in our producers’ living room, we had had grand schemes for shooting in far-away desert wastelands or on a friend’s farm outside of town (both were free options, and we had almost no money), but we soon realized we wouldn’t be able to catalyze the community if this wasn’t happening in our own backyard. Travel would be an issue. Enter Paul Savage, one of our early associate producers who stepped into the role of location liaison and construction coordinator. He suggested we rent the warehouse now known as 30 West in Oakland, which he was on the board of.

At the time, it had recently been secured by a group of artists who had recently been kicked out of another arts collective living in a warehouse in West Oakland, and was being used as storage for a deconstructed Burning Man art car. As our crew size outgrew the living room, we took a meeting in the freezing-cold, dilapidated, warehouse and immediately saw potential. This was finally becoming possible.

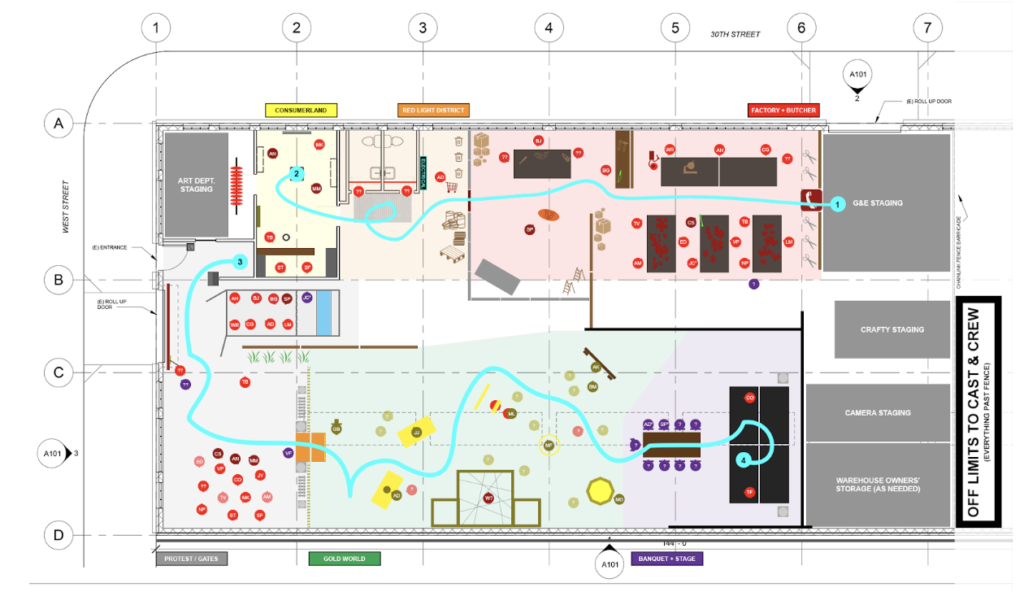

Our visions were endless but space was limited, so we had to be incredibly efficient. We used architectural drawings of the building to previsualize how and where each of the donated set walls could be placed, enabling us to make the most of the space. With careful planning, and a month of 7-day weeks and 16-hour days, we were able to fully construct all of the sets for each scene.

The finished set filled the entirety of the warehouse — the Red World, the Gold World, and a little sliver in the back for production and a fire exit. Our set was built as you it’s seen in the video, with some mad hustle by associate producers Alex Malek, Justin Laundre, and Trevor Banta in the final hours. You could walk the unbroken path of Pancho and the camera in a big “U” shape around the space. We split the shoot into two chronological days: the first half (Red World) and the second half (Gold World). The unused side of the set was filled with our hundred-plus working artists, their art, personal belongings, actors, additional props, wardrobe, makeup, and all of our film gear.

The majority of the lighting equipment was installed above the sets in a makeshift “grid,” allowing the sets to be pre-lit via scissor lift in the days leading up to the shoot. With all of the lighting units “in the sky” controlled wirelessly via iPad, the crew could move safely around the set. This saved us a ton of space, and quite a bit of time during filming as well, as we didn’t need to move lights between scenes.

Part of the pitch when we were corralling the community behind the project was a promise that we’d throw a great big cathartic party for everyone once we wrapped, and so once we knew we had it all “in the can,” the warehouse rapidly became a backdrop for a celebratory dance party. Champagne was popped. Tears were shed. Seeds were planted, and the warehouse is now a budding community housing dozens of local artists.